The Lost Township of Whitelachlens

A Mystery on the Moors

F22010, first published 11th May 2022

Heading out from Edinburgh along the Lang Whang, shortly before you enter the featureless conifer plantations of Camilty Forest, you pass by Halfway house (once a traveller's hostelry) and the lonely Brookbank cottage. Glance northward from here and there appears nothing more than a flat, featureless and boring expanse of rushy clumps and moorland. The little Whitelea burn winds it course across this wild scene, but is hidden in its steep-sided valley cutting into the soft sandstones and shales of the plateau. A high deer-proof fence was recently erected around these lands (presumably to protect yet another conifer plantation), so it no longer possible to pick your way along the old footpath that once crossed this mossy waste. From certain viewpoints however, with the aid of binoculars, it is still possible to spy a small, distant pillar of masonry, perhaps once the gable of a building, standing in isolated splendour in the middle of the moor.

The structure is marked as a ruin on the earliest Ordnance Survey map surveyed in 1852; part of a rather puzzling muddle of stone walls running from the level of the moor down the valley sides to the little burn. While the ruin is not named on the map, the OS surveyors noted that it was once a farm house named Whitelea, “which at one time had a farm attached which is now joined to Camilty.”

The farm is marked on several earlier maps, lying a good distance from the nearest road and often shown as multiple buildings. It's common to find that the spelling of a place name might change through the years, or be noted down differently from spoken accounts, however the variation in the spelling of this farm is quite phenomenal . Here's some of the spellings, and the date of the maps on which they appeared: Whitelochnees (1754), Whitelochley (1773), Whiteinchley (1807), Whiteloch Lees (1816), Whitelocklees (1817), Whitelochlees (1828), Whiteloch Inn (1850).

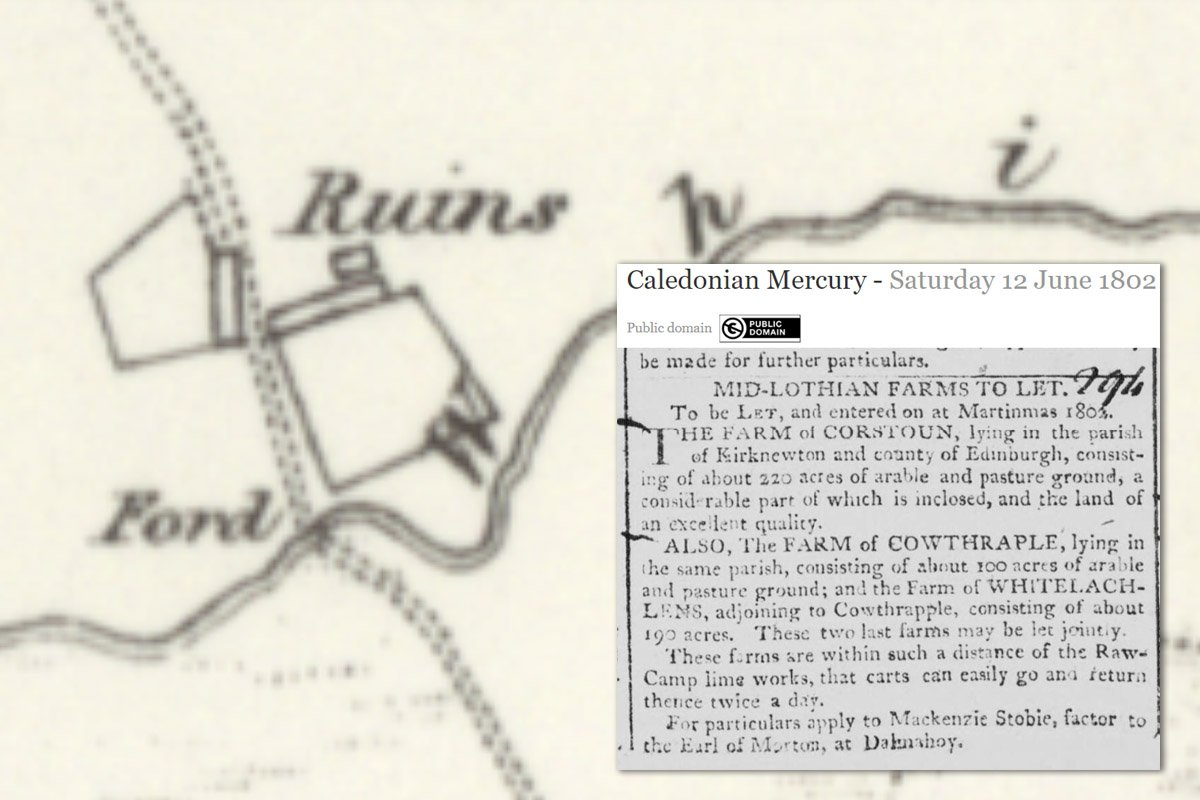

A still different spelling – Whitelachlens – was used when agents for the Earl of Morton advertised the property and neighbouring farms for let in 1802, and perhaps the landowner's spelling of the name might be considered the definitive one. The 190 acres of Whitelachlens formed the westernmost part of the huge Dalmahoy estate.

The earliest reference on a map is perhaps the most informative. Roy's map of the Scottish lowlands was surveyed in about 1754; just before the old ways of farming were swept by the agricultural improvements of the age of enlightenment. Roy's maps look a little random and sketchy, with various different scribbles suggesting hills and moss-land, and with areas of parallel scoring indicating the old unfenced fields of runrig cultivation. While not to be taken too literally, the scribbles suggest that Whitelachlens (here spelled Whitelochnees) consisted of a number of buildings and a few small open fields south of the burn, all surrounded by boggy wasteland and common grazing. All seems to have been abandoned a good time before 1852 when the OS map shows only a walled area providing shelter for animals and some ruinous roofless buildings.

6"OS map c.1854, and newspaper reference

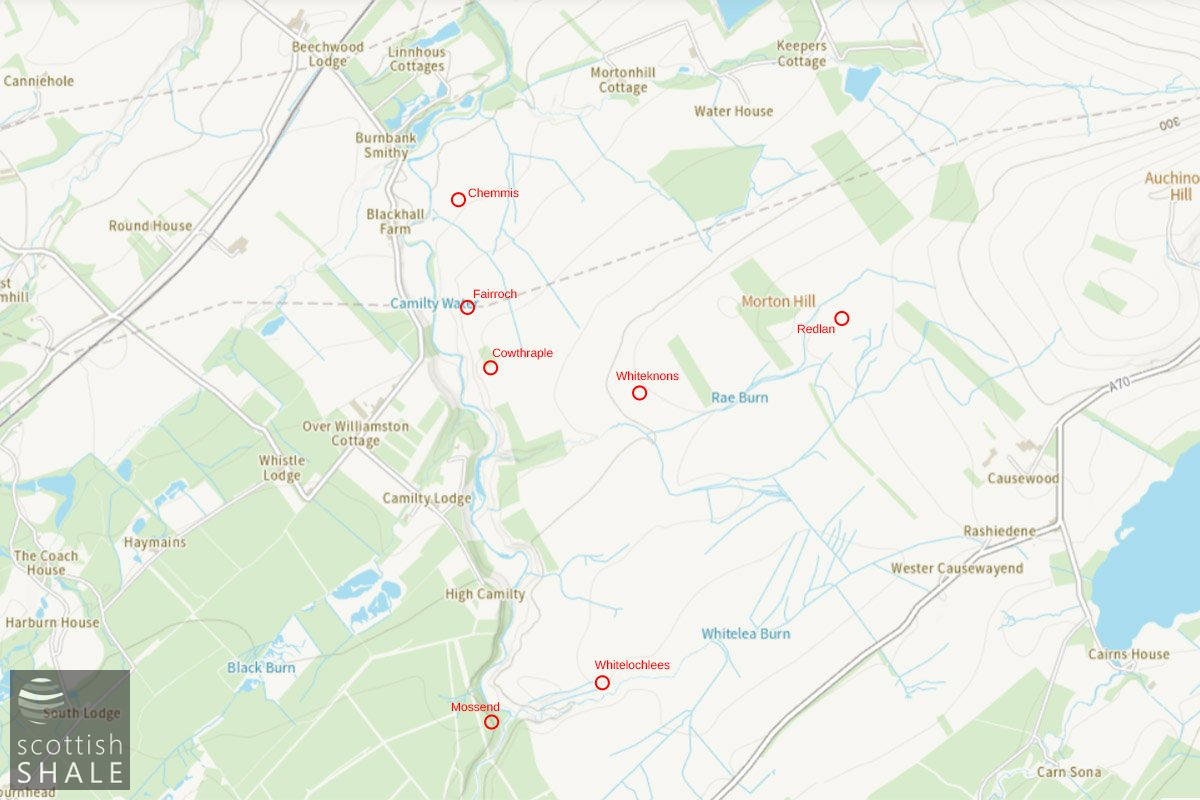

Location of the lost farms in the Dalmahoy estate

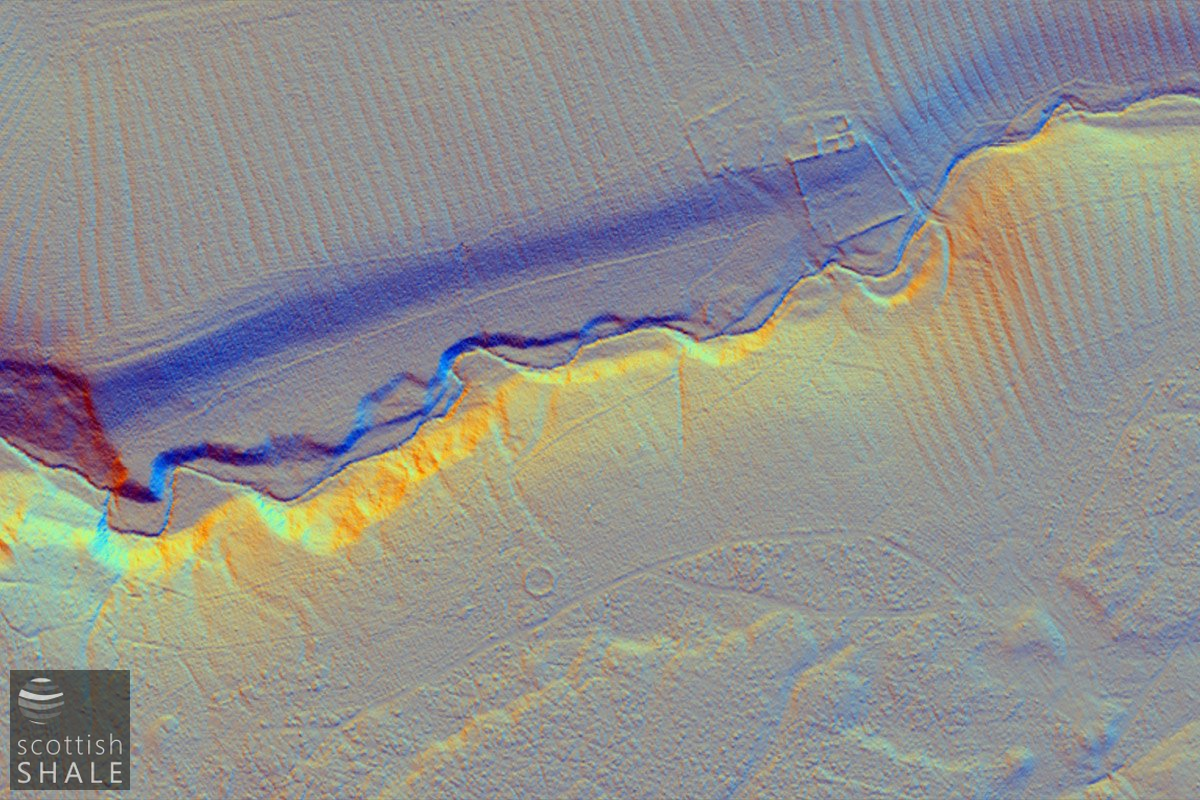

Lidar view of the Whitelachlens area

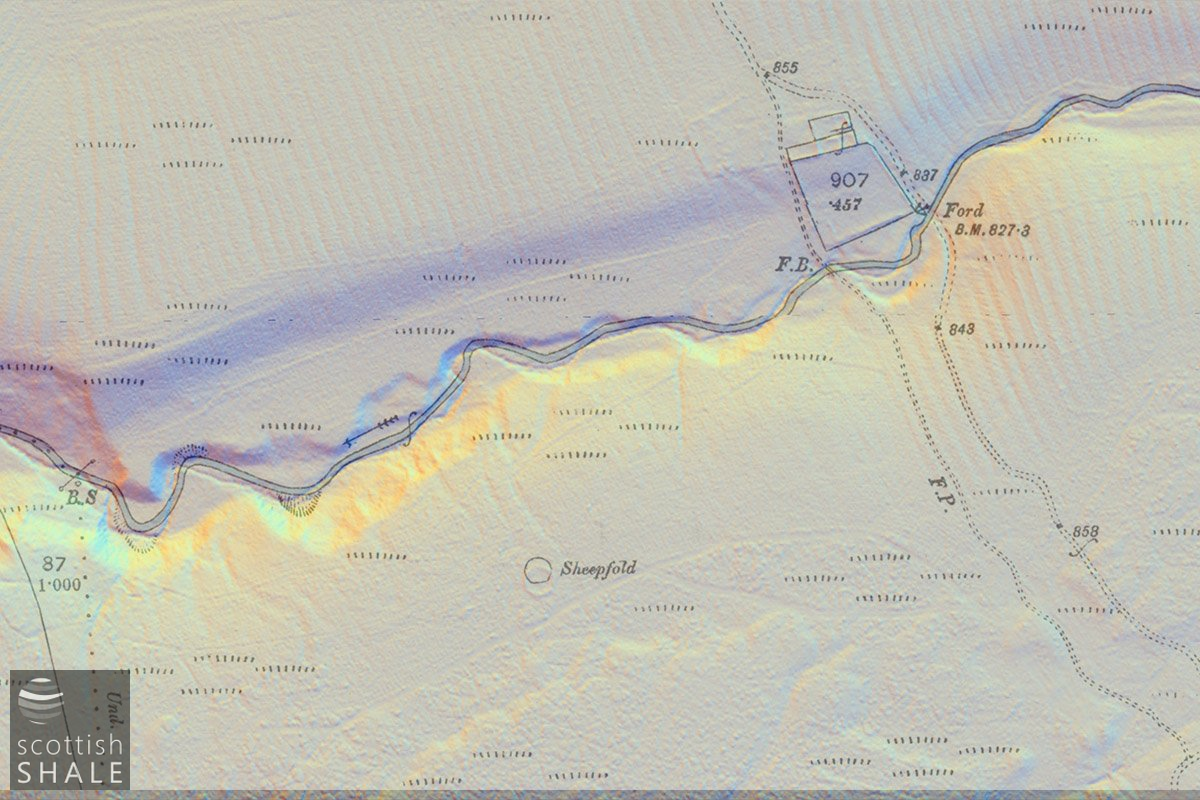

25" OS map overlaid on the Lidar image

Lines traced from the Lidar scan overlaid on an aerial view.

Parts of the site have been ploughed for forestry recently, throwing up parallel ridges of soil on which young trees are planted. Despite this disturbance, aerial Lidar surveys, (which map subtle bumps and hollows in the ground), reveal evidence of a township that were are not apparent on the ground and have not been recorded in earlier maps. In addition to surviving walls, the survey show features on the south side of the burn that coincide with the open run rig fields suggested on Roy's map. When staring at the Lidar image you begin to pick our rectangular shapes that might have buildings, boundaries of fields, the route of trackways – even a structure beside the burn that might have housed a primitive mill. However it's easy for the imagination to get carried away with this join-the-dots exercise, and only proper archaeology could separate facts from fancy. The evidence does however suggest that a small township or fermtoun once existed here, most likely with simple structures of stone and heather thatch housing a few peasant families who eaked a miserable existence at this wild and remote spot. Sheep will have been tended, and during the worst weathers would be sheltered between the long walled enclosure extending down the valley side. Their dung may have brought a little fertility to little patches of haughland beside the burn, or areas of moor to the south, where basic crops may have been grown.

Just as with the Highland clearances, many lowland settlements were wiped off the map during the late 18th and early 19th century centuries. In some instances communities were forcibly removed by an improving landlord, but in many, folk will have simply drifted away seeking kinder fortune elsewhere.

Armstrong's map of 1773 shows a string of farms, in addition to Whitelachlens , on the flat moorlands south of the Linhouse Water, and within the Earl of Morton's Dalmahoy estate. Unfamiliar place names such as Fairroch, Chemmis, Redlan and Whitenons disappeared from maps a few years later, and seem to have been subsumed with the improvement of the old Cowthrople farm, described in 1802 as 100 acres of arable land and pastures. A “thrashing machine” at Cowthople marked on the 1856 map show that the former moorland was then yielding cereal crops. This progress seem to have been temporary however as by 1895 Cowthrople was a ruin and most of its land seem to have reverted to sheep and shooting.

Although Whitelachlens appears to have been abandoned as a farm at some time around 1840, it is marked as “Whiteloch Inn” on a map of roads published ten years later. This could be just another mistake in transcribing the name, or it might indicate that it served for as a time as hostelry. The little settlement lay at a natural crossing point of the little Whitelea burn, while the valley would have provided welcome shelter when driving cattle to markets of the south across the Cauldstane Slab. In these remote parts, many old buildings are associated with the folklore of the cattle drovers. It doesn't seem that far fetched to imagine herds of black cattle enjoying the sparse pasture of the moorland common grounds, while comforting ale was quaffed within the shelter of Whitelachlens' walls.

View through the deer fence showing ruins of Whitelachlens, with two walls running between the level surface of the moor and the burn

A closer view of the ruins, looking towards Causewood farm

Further close up of the ruined gable end ? at Whitelachlens

The valley of the Whitelea burn looking towards Whitelachlans, with the ruin visible in the centre of the image.