The Five Sisters Bing

A history of Westwood Bing

F21001, first published 28th March 2021

From some angles it appears as if a huge knuckle has been thrust upwards by some giant creature slumbering beneath the earth. From any direction the regular lines of the five sisters bing stand out from the natural curves and slopes of the landscape, and despite an ever-deeper cloak of grass and scrub, it is clearly a monument that was placed there by man and machine.

Since 1995, Westwood Bing (a.k.a the five sisters) has actually been a scheduled monument and is now protected for posterity. They’ve become a symbol of West Lothian, and a memorial to the shale oil industry, yet the famous five-leafed bing is an oddity, a one of a kind.

Prior to the second world war, bings were built by men. Hutches, each containing a ton or two of spent shale, would be drawn up the slope of the bing by a wire haulage rope, then released at a level platform near the top of the incline. From here, men pushed and trundled the hutches along rails to the edge of the bing where, with huge effort, they lifted one end of the hutch so that its contents cascaded down the face of the bing in a cloud of dust. The rails were repositioned regularly to spread the tipping, often fanning-out from a central point to create great lobes of material. These manual techniques determined the shape of a tradition shale bing, With distinctive steps and intersecting lobes they look strangely organic when viewed from the air, almost like a set of lungs.

A view from the early fifties with spent shale being tipped on the two outer bings. In the foreground is the conveyor from the retorts. LVSAV2019.120

Another early fifties view, with two bings being created. LVSAV2019.119

Westwood bing looks very different because it was built by machines. All features of the Westwood works were very different to everything that had come before. Built to fuel Britain’s war machine the designers of Westwood works took full advantage of the technical advances that had taken place since the previous new oil works almost forty years before. This new technology extended to the disposal of the spent shale from the efficient new retorts. This finely graded waste was transported along a conveyor belt to a central bunker from where the spent shale was fed to a large carriage on rails. This was hauled to the top of the bing where the carriage was discharged by gravity.

This allowed a huge saving of labour, and created a very different shape of mound to the traditional shale bing. Perhaps because the shale was broken to a smaller size and more bound oil was extracted during retorting process, the Westwood bing supports vegetation more readily and have greened much faster than other shale bings.

Beginning during World War Two, the two outer bings were first to be formed, set at about 60 degrees to each other and defining the limits of the tip. The southernmost bing buried the heap of mine waste from the old Westwood No. 12 pit. By the early 1950’s the rails had been removed from the outer bings and tipping begun to fill the space between the two outer “sisters”. Two long tips were formed merging with the outer bings, with a short stubby fifth bing extending between them. When Westwood oil works closed in 1962, marking the end of the Scottish shale industry, the middle sister still retained space to grow.

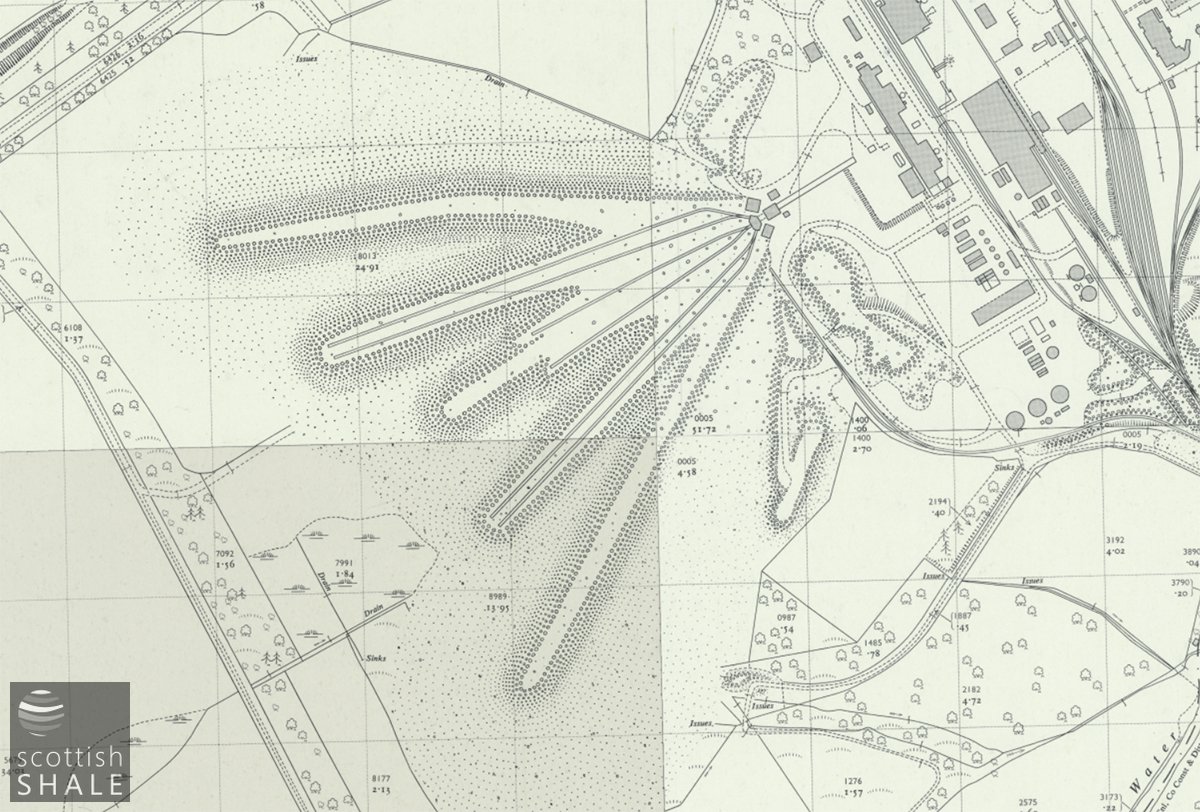

1:2500 OS map c.1958, courtesy of National Library of Scotland. The rails have been lifted from the two outer bings.

Aerial view

RAF aerial reconnaissance view c.1950, with rails apparently still in place on the outer bings, but material also tipped in the middle bings

Aerial view c.1950 overlaid with 1895 OS map showing the location of Westwood House

It’s a popular romantic notion that a mansion lies buried beneath the middle bings, conjuring up images of chandeliers and sherry decanters being engulfed by a tidal wave of spent blaes. The central part of the bing certainly occupies the site of Westwood House, the fine home of Captain Robert Steuart, who had once operated his own oil works in a distant part of his estate. The house had seen better days by the time it was bought by the Oakbank oil company prior to World War Two and was subdivided into a number of homes.

It seems likely that with wartime shortages, the materials of Westwood House were carefully reclaimed prior to burial of the site. When aerial photographs were taken a few years after the war, the house site was already submerged in waste, but the location of the associated estate offices remained exposed. From what can be made out from the black and white RAF reconnaissance photos, the buildings here had been dismantled down to foundation level.

Following the closure of Westwood in 1962, the oil works site was sold and new industrial purposes found for many of the buildings. In an age of motorway building there was a ready demand for spent shale to form embankments and earthworks, however in 1968 and on subsequent occasions, planning permission to quarry the bings was refused. There were mixed views on their future. One letter to the editor described them as “a blight on the landscape and contributing to the reputation of West Lothian as being a dirty, unattractive and industrial county”. Others saw them as a memorial to the last generation of shale workers. Gradually an affection grew for the giant landforms, which became increasingly referred to as the Five Sisters, rather than the more prosaic Westwood Bing. To their credit, the authorities boldly resisted calls for the removal of the sisters, and even supported their recognition as a piece of landscape art. These efforts eventually led to their designation, in 1992, as a Scheduled Monument protected by the full force of the law.

The Sisters remain in private ownership, and access is discouraged. Without hikers boots or swarms of trail bikes they grow a denser cloak of grass and shrub every year. Athletic cattle sometimes find their way up the lower levels of the bing in search of rare and tasty vegetation, but seem to do little damage

About a decade ago, for reasons that are unclear, a roadway was cut around the base of the bings, nibbling away at the sisters’ petticoats, and potentially destabilising some faces of the tip. An enforcement order was issued which prevented further damage, but it is clear that vigilance is needed to ensure that our sisters remain in the best of health.